Women’s Rights

I cannot remember the time when I did not think women ought to vote. The old Anti-Slavery struggle, which was the educator of so many of us, was at its height in my childish days; and the arguments for the freedom and equality of all men before the law which I heard so frequently at home, in public meetings, and through the press, were my earliest intellectual stimulus. Instinctively I applied the same reasoning to women. Hence the equal right of Woman to social, civil and political equality, has always been to me like an axiom which it were as idle to dispute as to undertake to controvert the multiplication table.

Lavinia Goodell, November 2, 1875

Lavinia was an active member of the 1870s “Woman’s Rights” movement. She recalled that suffrage was just one of the rights at issue. Women also claimed the “hotly and fiercely contested” right to “speak in public before promiscuous assembly,” the right to equal wages for equal work, the right to enter professions, the right to hold property after marriage and to divorce. Id. Lavinia published many articles on women’s rights in the national press. Her positions on some of these issues, with links to a few of her articles and speeches, appear below.

Right to Vote

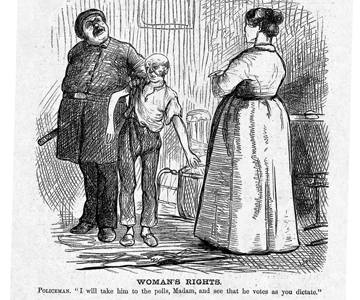

For most of 1871, Lavinia lived in New York and worked as an editor for Harper’s Bazar. During this time, she wrote a series of articles on suffrage in the Woman’s Journal,a weekly women’s rights periodical that Lucy Stone and her husband, Henry Brown Blackwell, began publishing in 1870. In those days, many men and even many women objected to giving women the right to vote for reasons that sound preposterous to the modern ear. In four erudite, yet saucy, articles Lavinia dismissed the prevailing objections to “womanhood suffrage”: (1) “woman would ‘unsex’ herself by participating in the duties of public life”; (2) “woman’s influence would be bad”; (3) “granting suffrage to woman would inaugurate a ‘tremendous social revolution'”; (4) “man represents woman”; (5) “woman’s influence is already so great that she need desire no other”; (6) “the ballot will be of no assistance to working women”; and (7) “woman does not desire the ballot.” Read Lavinia’s series of articles, titled “Womanhood Suffrage: A Review of Objections,” here: first article, second article, third article, fourth article.

Just a few years later, Lavinia lampooned the prejudice against women’s suffrage, which by then had started, very slightly, to wane. She wrote: “It was once a powerful argument against Woman Suffrage, that if women voted they would have to be voted for to hold office and then the heavens would certainly fall! Pictures of coarse, unsexed, masculine women, meek and suffering husbands, and neglected children were sketched ad infinitum, till we all closed our eyes and shuddered in holy horror.” Read Lavinia’s article, “Advanced Principles,” here.

Right to Equality in Marriage

For a woman who never married, Lavinia held firm views about the relationship between husbands and wives. In the 1870s, a wife was generally expected to be subservient to her husband in all matters. Marriage and equality were considered incompatible. Suffragists, in contrast, saw marriage as a union of equals.

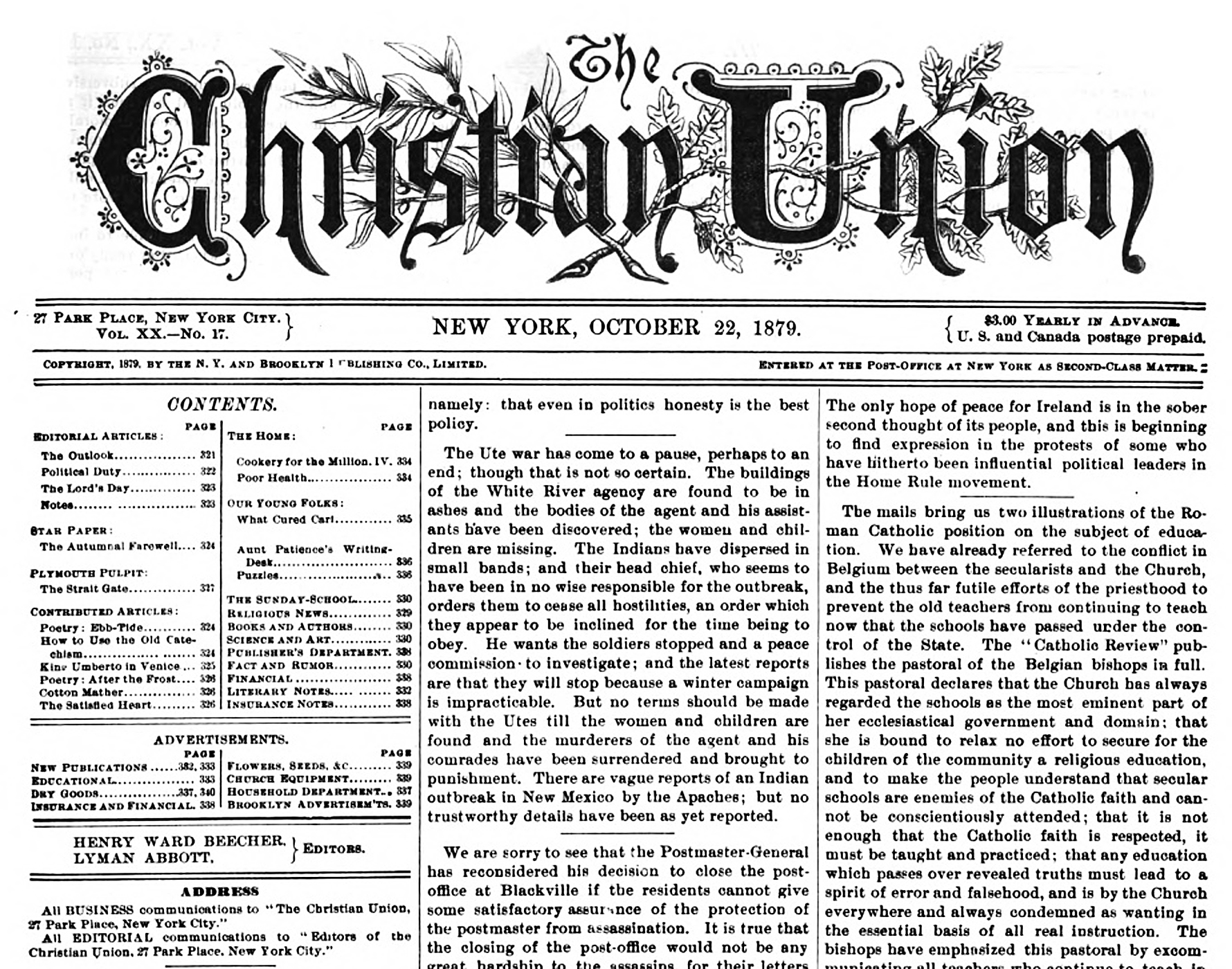

In 1879, Lavinia clashed with the Christian Union, a leading, religious paper generally favoring equal rights. The Christian Union exhorted wives to submit to their husbands because “[a] two-headed creature is always a monstrosity.” Lavinia shot back: “The wise woman will not always ‘submit.’ She will have, if necessary, a contest, short, sharp and decisive, which shall be followed by a peace based on equality, rather than live a life of degrading and humiliating submission in that home of which she is called ‘queen.'”

In a debate that spanned a half dozen articles, the Christian Union argued one side, while Lavinia published rebuttals in the Woman’s Journal. The Christian Union declared that wives should defer so that children do not witness strife between their parents. Lavinia replied that husbands and wives should model a mutual respect that their children could emulate among themselves, with their future spouses, and with members of the opposite sex generally. In her view: “There is no reason why [a husband’s] trust, his love, or his self-abnegation should not be as great as [a wife’s]; and only where it is can there be perfect harmony.” Follow the debate between Lavinia and the Christian Union by clicking on these articles: “The Way to Peace,” “Spherical Domesticity” in the CU, “Spherical Domesticity” in the WJ, “Submission or Equality,” and “Spherical Domesticity Again.”

Right to Enter Professions

If the law of nature destined women to be subordinate to, and dependent on, men, then they could hardly engage in professions together. That would make them equals. Naturally, Lavinia was all for it. By becoming doctors, lawyers, ministers, and so forth, women could develop their minds, support themselves financially, and improve the professions they entered.

In 1872, prominent American clergymen, progressive enough to have supported abolitionism, declared in the national press that preaching was an exercise of authority belonging only to men. Lavinia rebuked them: “‘Usurping authority’ is the anguished cry of panic stricken clergy. And ‘usurping authority’ means, in plain English, merely asserting equality. Were women to forbid men to preach, telling them their sphere of duty lay in their workshops, or on their farms, and that as Christ rules the church, the woman is to rule the man,’ this would be a usurpation of authority.” Read Lavinia’s arguments in support of women ministers in “A Reason Why,” “An Irruption of Depravity: Women in the Pulpit, a Presbyterian Protest,” and “A Church Movement,” which were all published in the 1872 Woman’s Journal.

Lavinia is best known for opening the practice of law to women in Wisconsin. But she championed the idea of women lawyers in the national press too. In 1876, she wrote a long (11 pages, single-spaced) paper called “Woman in the Legal Profession,” which was read at the Fourth Woman’s Congress in Philadelphia. Point by point Lavinia dismantled the common objections to woman lawyers: 1. Women lack mental discipline. All the more reason to study law, she said. 2. Hearing men discuss unpleasant subjects in court would degrade women. Nonsense. Female parties and witnesses already hear them, she replied. Besides, women need knowledge, not ignorance, of the world’s vices in order to combat them. 3. Women lawyers will exert their feminine influence over opposing counsel, judges and juries thereby undermining the administration of justice. No problem, she said. Put women on the bench and in the jury box too.

The photograph above is of Belva Lockwood and Olympia Brown. Belva (left) was the first woman lawyer to argue to the United States Supreme Court and the first woman to run for president. Olympia (right) was the first ordained minister in the United States. Lavinia corresponded with both women.

Rights of Married Women

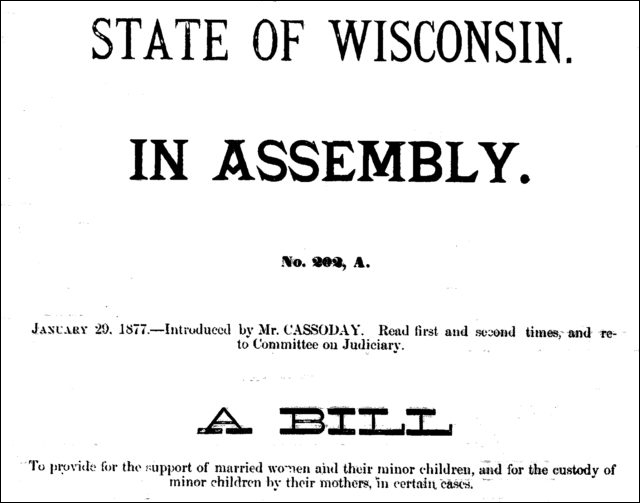

Lavinia believed that female lawyers were in the best position to discover and address inequities in the law that harmed women. She herself represented women in divorces and property disputes and was especially troubled by the laws governing a married woman’s property rights and child custody. In her speech to the Fourth Woman’s Congress mentioned above, she pointed out that when a man deserted his wife, she could not use his property to support herself and their children. The town took the property and forced the wife and children to live in a pauper house, which the town supported.

Lavinia not only tried to correct this injustice in her court cases, but also by drafting a bill “to provide for the support of married women and their minor children, and for the custody of minor children by their mothers, in certain cases.” The proposed law would give a married woman, whose husband either from drunkenness, profligacy or other causes, refused to support her and their children, the right to petition the court for permission to take possession of his real and personal property for financial support and for custody of their children. A husband affected by such an order could petition to have it modified or set aside. Lavinia persuaded John Cassoday, speaker of the Wisconsin State Assembly in 1877 and later a Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice, to introduce the legislation. It does not appear to have passed. You can read Lavinia’s bill here.