“The devil has come down in great wrath knowing that his time is short.”

Lavinia Goodell, February 29, 1872

In early 1872, media accounts – especially on the east coast – were abuzz with the scandalous story that a woman had been allowed to preach in a Brooklyn Presbyterian church. The brazen woman in question was Sarah Smiley, a Quaker.

Ms. Smiley was born in Maine in 1830. She initially wanted to become a teacher but after the Civil War went South to “relieve human suffering.” She later began speaking to audiences and eventually was invited to speak in liberal-minded churches. In January 1872 she became the first woman to ever speak in a Presbyterian church when Rev. Theodore Cuyler invited her to address his congregation in Brooklyn. Rev. Cuyler had lived with Quakers and had been invited to address a Friends revival meeting in Brooklyn, so in return he invited Ms. Smiley to speak from his pulpit on a Sunday evening.

By all accounts Ms. Smiley’s address was well received (she spoke about the vision of Jacob wrestling with an angel), and it is unlikely that either she or Rev. Cuyler could have anticipated the firestorm that soon followed. Two days after the event a scathing letter signed by Jon Edwards appeared in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Mr. Edwards accused Rev. Cuyler of “degrading the teachings of St. Paul.” He wrote:

This is no time to encourage even in the remotest way the pretensions of those graceless women who are engaged in the unholy work of turning society upside down, and whom I hear in our families and social gatherings, ridiculing St. Paul as an old Jewish bachelor, unworthy of respect.

Edwards’ diatribe was just the beginning. The floodgates opened, and New York area newspapers were filled with letters and opinion pieces on both sides of the question of the propriety of women preaching. The New York Daily Herald ran a series of columns noting that the staid Presbyterians of Brooklyn “were shaken from hats to boots as by an earthquake.” The Herald praised Ms. Smiley, saying she had “taken Brooklyn by storm” and that “for real power and efficiency in the pulpit it is said that Miss Smiley has hardly an equal in the Christian ministry today.”

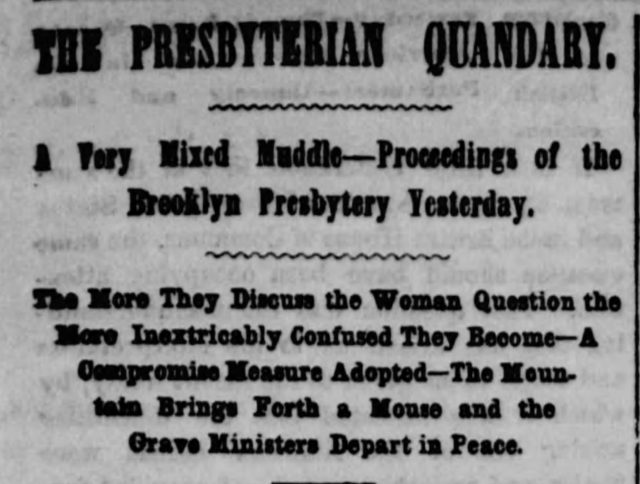

Presbyterian elders were sufficiently outraged at a woman invading one of their pulpits that they held a special meeting to discuss the issue. The Daily Herald ran this headline:

After at least two days of discussion, the Presbytery adopted a resolution saying that while “meetings of pious women by themselves for conversation and prayer” were approved, “to teach and to exhort, or to lead in prayer in public and promiscuous assemblies is clearly forbidden to women in the holy oracles.” Far from ending the discussion, the resolution spurred columns of additional ink. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle ran a letter to the editor that soundly criticized the Presbytery’s actions and said, “Miss Smiley will not do as much harm in preaching as they in suppressing her.”

On February 11, 1872, Henry Ward Beecher, whose Brooklyn church Lavinia Goodell sometimes attended, injected himself into the “should women preach” question and “preached one of his boldest sermons.” Not surprisingly, Beecher showed himself to be a staunch supporter of Ms. Smiley and Dr. Cuyler. The Daily Eagle reported that Beecher:

Came squarely up to the Presbyterian blunder and asked, sarcastically, had Miss Smiley horns or hoofs that his brethren were so much afraid society would tumble to places because she preached in a church? She did not preach treason; she simply told the story of the Cross. Her right to preach to ten or twenty-five was not questioned; why should her right to preach to a thousand be?

By coincidence, Lavinia Goodell’s friend and mentor, Deacon F. S. Eldred was in Brooklyn at the time and heard Beecher’s sermon.

Lavinia, who had moved from Brooklyn to Janesville, Wisconsin the previous fall, and who was an avid believer that all professions should be open to women, followed Ms. Smiley’s saga with great interest. In a letter to her cousin Sarah Thomas, Lavinia expressed surprise at how the Independent newspaper came out strongly against women. Lavinia said, “The devil has come down in great wrath knowing that his time is short.” Lavinia wrote several articles for the Woman’s Journal advocating for women in the pulpit. The first appeared on March 23, 1872 and specifically mentioned the drama swirling around Ms. Smiley. She began, “ Miss Smiley, preaching in Dr. Cuyler’s pulpit, seems to have shaken ecclesiastical authority, as the nailing of Luther’s theses on the church door shook the Papal throne.” Read the entire article here.

Lavinia Goodell continued to advocate for full equality for women in all the professions for the remainder of her life. Read more here.

Sources consulted: Lavinia Goodell’s letter to Sarah Thomas (February 29, 1872); Harper’s Weekly (March 2, 1872); Brooklyn Daily Eagle (January 16, 1872; February 9, 1872); New York Daily Herald (February 4, 1872; February 6, 1872; February 7, 1872) ; Woman’s Journal, vol. 3. NO. 12, 3/23/72, seq. 98, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University; https://www.wamc.org/show/51/2022-04-11/51-1706-womens-history-month.