Spinsterhood: the fate of an unattractive woman or a radical act?

Have you seen the Little Women movie? The new ending would have incited Lavinia Goodell to dash off an op-ed for the Woman’s Journal.

Greta Gerwig has Jo March telling an editor that her heroine was adamantly opposed marriage, so the novel would not end with her wedding either Laurie or Professor Bhaer. The editor shot back: “Who cares! Girls want to see women married, not consistent. If you end your delightful book with your heroine a spinster, no one will buy it. It won’t be worth printing.” For Wisconsin’s first woman lawyer, “them’s fightin’ words!”

Lavinia (1839-1880) and Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888) were contemporaries. In fact, Lavinia met Louisa’s father, Bronson Alcott, a 19th century educator, abolitionist, women’s rights advocate, and co-founder of “Fruitlands”—an agrarian commune based on transcendentalist principles. In January 1875, Bronson gave a parlor lecture in Janesville about New England authors. Lavinia attended.

We don’t know whether Lavinia read Little Women, but her letters and diaries note that she enjoyed an unnamed novel Louisa published in 1873. Judging from dates, it was likely Work—a Story of Experience which concerned a young woman struggling to support herself outside the home during the aftermath of the Civil War. In the end, the heroine becomes an activist for working women.

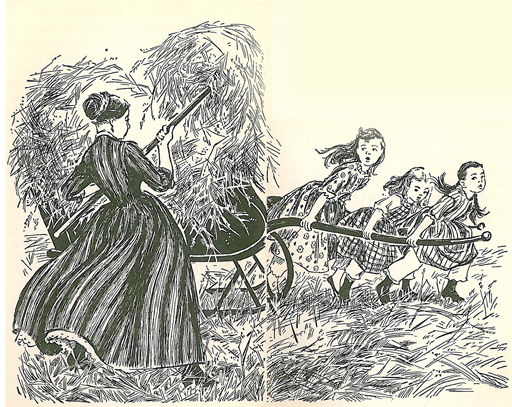

Lavinia also read Louisa’s Transcendental Wild Oats published in the Woman’s Journal in 1874 (read it here). Oats was a thinly-disguised satire about Louisa’s father, his business partner, and her mother (named “Sister Hope”) and their involvement in “Fruitlands.” The piece portrays the men as feckless dreamers and “Sister Hope” as the hard-working savior of the family and the community.

Lavinia told her sister:

If convenient, return the [Woman’s Journal] containing the story by Miss Alcott entitled “Transcendental Wild Oats.” It is a splendid story and I hope you have read it; if not, do before returning it. I suspect it is the true story of the “Brook Farm and community” Bronson joined, and the four little girls were Miss Louisa Alcott and her sisters. I think I recognize also some of the other characters. I want to show it to some friends here, and then send it to Sarah.

Plots involving independent women saving themselves, their families and their communities would have tremendous appeal for Lavinia. She and Louisa were women’s rights proponents and opposed to marriage. Louisa, according to Gerwig’s adaption of Little Women, saw marriage as “always an economic proposition”—a way for women to achieve financial security.

Lavinia would have agreed but also highlighted the legal ramifications of marriage. The institution made a woman the subordinate of her husband, deprived her of property and other legal rights, and could cost her custody of her own children. If a woman chose a spouse unwisely, she could wind up in a pauper house. See Women’s Rights page.

At 19, Lavinia declared:

I don’t believe in living to get married, if that comes along in the natural course of events—very well, but to make it virtually my end aim, to square all my plans to it, and study and learn for no other purpose, does not suit my ideas.

Still confident in her views at 22, she published “Old Maids,” an essay challenging conventional wisdom about spinsters:

I love old maids—I do! They are decidedly the most excellent portion of the community, the cream of society, the very salt of the earth! Who is the heart, the soul, and life of the Benevolent Society? The old maid. Who makes the home circle, and her own, sunny and joyous, through her kind care and forethought? The old maid . . . Who is to be depended upon to undertake what must be done, and nobody else will do? In short, who is the most unselfish of mortals? The old maid—god bless her!

To Lavinia, the “careless and unfeeling manner” in which people spoke of spinsters was “beneath contempt.”

Must she be despised who withholds her hand because she cannot give her heart; and she esteemed who, for a home, a name, a station, weds one whom she cannot love? Rather, all honor to the woman who holds marriage as a thing too sacred for speculation or barter.

She was quite serious on this point. Clarissa (her mother) reported to Maria (her sister):

Lavinia thinks if she was going to be married she should want to live two years with the person before venturing on so important an event. She finds we must live with anybody to know them . . . I tell her I think she must believe in the doctrine of total depravity by this time.

In the 19th century, spinsterhood was seen as the fate of an unappealing woman. But it was also an act of radical feminism. It’s now 2020—152 years after Louisa May Alcott wrote Little Women. Is Jo’s editor right: spinsters don’t sell? If you would read a novel or see a movie about a strong-minded woman who chose not to marry, please like Lavinia’s Facebook page and tell us your favorite 19th century spinster!! CB

Sources Consulted: Clarissa Goodell’s letter to Maria Goodell Frost, February 20, 1868, Lavinia Goodell’s letters to Maria Frost, April 6, 1873 and March 16, 1874; “Old Maids,” Principia (Dec. 28, 1861); Lavinia Goodell’s Diary, January 18, 1873, Maria Goodell Frost, Life of Lavinia Goodell (unpublished manuscript).