Reclaiming criminals: “My remedies will either kill or cure!”

Lavinia was quite taken with James Tolan, her client accused of stealing a $23 watch. “I never had the confidence of a criminal before,” she told her sister. “It was a very interesting experience.” Poor Tolan, an inmate of the Rock County jail, was literally a captive audience. Lavinia visited him often and, in her words, “persecuted him nearly to death” with lectures, tracts and sermons. She declared: “my remedies on him will either kill or cure!” Lucky for Tolan, Lavinia’s courtroom zeal matched her determination as a reformer.

To set the stage, Lavinia had to try two cases the week of November 17, 1875. She defended Tolan, the watch thief, on Tuesday and Cramer, the spoons and jackknives thief, on Thursday. At this point in history, respectable women did not go to court, and only two or three women lawyers in the country had ever tried a case (let alone defended a criminal). Lavinia was a novelty. A number of local women came to observe her in action. She told her sister: “I have quite introduced a fashion here for ladies to attend court.”

Tolan’s version of events was a hard sell. He had no money, loved strong drink, and spent most days “tramping.” One night he and some companions got drunk and a watch was stolen. When Tolan woke from his stupor he found the watch in his pocket but did not know how it got there. He knew he should have taken it to the authorities, but didn’t. He was charged with “larceny from the person.”

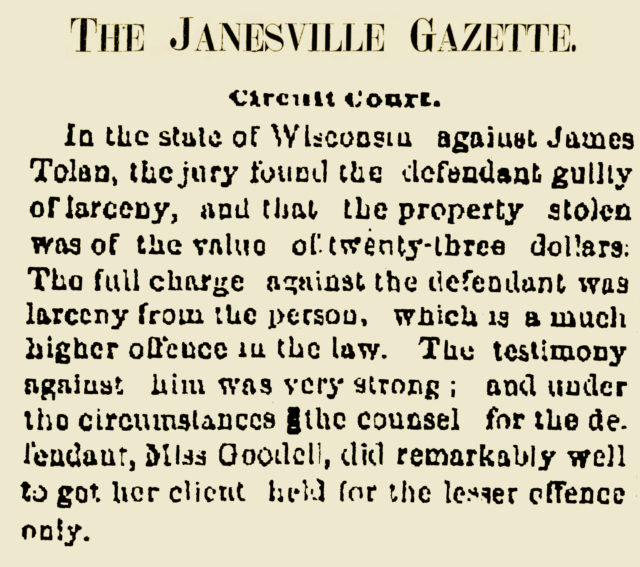

At trial, one companion testified that Tolan had confessed to stealing the watch. Another witness testified that the companion was the real thief. As the watch was found on Tolan, Lavinia did the best she could—she argued that he was at most guilty of simple larceny which carried a lighter sentence than larceny from the person. The jury sided with Lavinia. The Janesville Gazette reported that the case against Tolan was “very strong.” Under the circumstances, “Miss Goodell did remarkably well to get her client held for the lesser offence only.”

Her defense did not end there. She wanted the lightest sentence possible for Tolan, so she did something unfathomable to lawyers today. She sent a letter to Judge Conger asking for a brief meeting before he sentenced Tolan at any time or place the judge chose. There were matters worthy of consideration that did not come out at trial, she said. The judge replied that he would speak with her immediately before the sentencing at 2:00 on Saturday November 20th.

In the meantime, Lavinia had to defend Cramer. The merchant who accused Cramer of theft testified against him, but Lavinia proved that he came by the goods honestly. To her relief, the jury acquitted him. She believed him innocent and would have felt culpable if she had not been able to clear him.

That was Thursday. Lavinia still had to prepare for Tolan’s sentencing on Saturday. She had written to Tolan’s former employers asking would for letters attesting to his truthfulness and good character, but none had arrived. So she persuaded the judge to postpone the sentencing to December 1st. By then she had secured several testimonials. The judge gave him a stern lecture and a light sentence–3 months in the county jail instead of a prison sentence. In a follow up “My Tramp” article for the Christian Union she reported: “His heart is reached now, his conscience awakened, his whole manhood aroused. Is he saved? I hope and fear.”

Lavinia the temperance crusader had a soft spot for vagabonds who claimed to have been orphaned and then broken by alcohol. She regarded liquor as the root of evil and argued that, in refusing to shut down saloons, society injured men like Tolan more than he ever injured society. She firmly believed that these men could be “reclaimed,” and she spent the last few years of her life working toward that goal.

Sources consulted: Lavinia Goodell, “My Tramp,” Christian Union, December 15, 1875; “Circuit Court,” Janesville Gazette, November 16 and 18, 1875; Lavinia’s letters to Maria Goodell Frost (one dated November 18, 1875 and the other undated but describing these cases); Lavinia’s letter to Judge Harmon Conger and his response, November 16, 1875; Lavinia Goodell’s Diary Nov. 19 and Dec. 1, 1875.