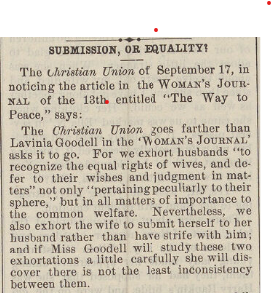

“Little by little, but all the time, we are gaining essential rights.”

Woman’s Journal, March 1877

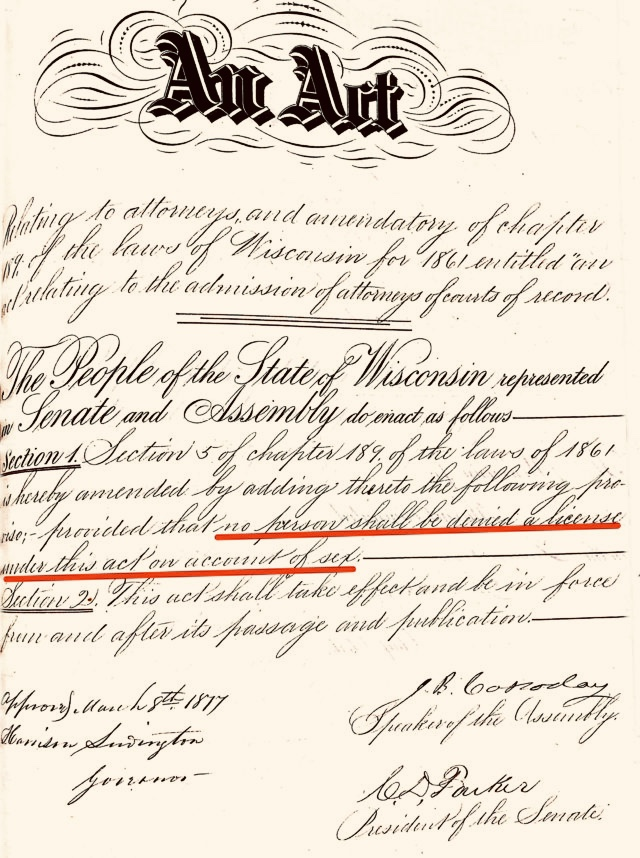

March 8 is Women’s History Day. By happy coincidence, March 8 is also the anniversary of the day that Wisconsin’s governor signed into law legislation drafted by Lavinia Goodell allowing women to practice law in the state.

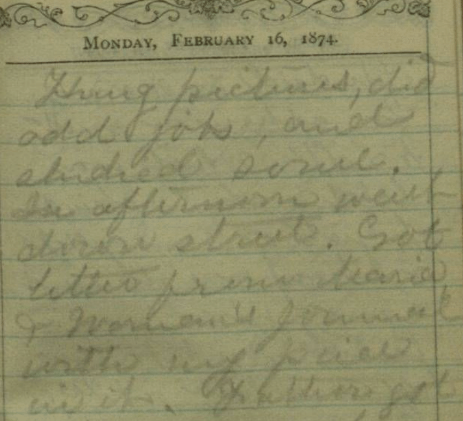

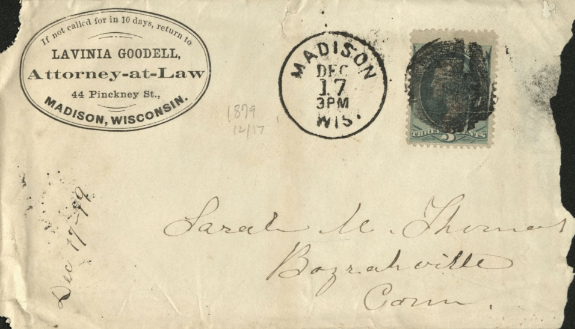

After Lavinia’s petition to be allowed to practice before the Wisconsin Supreme Court was denied in early 1876 (read more about that here), Lavinia drafted legislation that permitted people of both genders to practice law. Her Janesville colleague John Cassoday , who was speaker of the assembly, introduced the bill for her. In early 1877, Lavinia took the train to Madison where Cassoday introduced her to legislators, although the meetings apparently got off to an inauspicious start. On February 6, Lavinia noted in her diary, “Spent a stupid afternoon in Cassoday’s room waiting for men to come to me and finally had go to them.”

Continue reading →