“Miss Eveleth & Carrie Jocelyn are off for Beaufort, S.C. to teach the contrabands.”

Lavinia Goodell, January 11, 1864

Prior to the Civil War, it was illegal for enslaved people to learn to read or write. Beginning in 1863, Freedmen’s schools were created in areas occupied by Union forces to provide education for newly freed Blacks. (The Blacks were referred to as “contrabands of war.”) Lavinia Goodell, who grew up in a staunch abolitionist family, knew several women who taught at Freedmen’s schools.

In early 1864, Carrie Jocelyn and Emma Eveleth, two of Lavinia’s friends from Brooklyn, traveled to Hilton Head island off the coast of Beaufort, South Carolina, to teach at two Freedmen’s schools. The schools were run under the auspices of the American Missionary Association.

Caroline Jocelyn was thirty-three years old and single. Her father, Rev. Simeon S. Jocelyn, was a Congregationalist preacher who strongly believed that enslaved Blacks should not only have their freedom, they should also have the vote. Rev. Jocelyn was a good friend of the Goodell family and a founding member of the American Missionary Association. Carrie was accompanied by Emma Eveleth, a fifty year old single woman. At Hilton Head, Carrie and Emma first taught at Seabrook School, then at Stoney School.

Seabrook School was located on Elliott’s Plantation. Emma Eveleth’s report on their first several months’ work at the school was published in The Principia, the anti-slavery newspaper edited by William Goodell (with significant contributions by his daughter.) Emma wrote:

We hold our school in a large building formerly used as a cotton house. We are unfortunately destitute of benches. When we first came here the majority of the children sat on the floor,… Mr. F. procured a few boards to make benches with, … but the officials told him not to be any more expense to the government so the benches are not made and we have to place the boards on boxes. Boxes, however, are not over abundant, so we have not many seats.

I had about forty scholars and managed them very well. First, I read to them from the Bible and required them to repeat the Lord’s prayer. I then asked them questions in Arithmetic. Next, they sang “The Golden Shore.” They are very good singers and very fond of music.

The man whom Mrs. B. employs [in her home] is known by the revered name of Abraham. He had a hard time escaping from slavery, which he did over four years ago, concealing himself in the swamps…. Escaped slaves in the swamps are numerous, and they still continue to come to us as they find their way. Some of them are in a most forlorn condition.

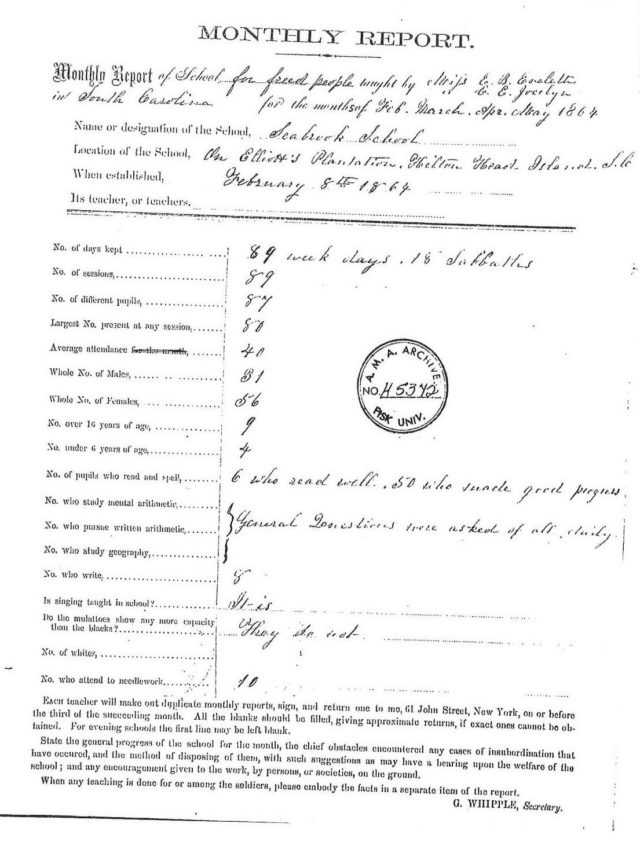

Here is a report that Carrie and Emma wrote providing statistics of their first four months of teaching:

Teachers’ living conditions were primitive, and the work was physically and mentally exhausting. In an 1865 letter Emma Eveleth reported:

We have some very cold weather & have not been able to get a stove, but have gone every day to school, & when it was very cold we have had some general exercises, then dismissed them, for the little creatures were not dressed very warm, and would shiver with the cold, but they could not bear to give up a lesson, and all were willing to stay & shiver till they said their lesson. I felt sorry to dismiss them without a full lesson they are so anxious for it.

After the Civil War ended, Carrie Joycelyn and Emma Eveleth taught at freedmen’s schools in Florida, including the Union Academy in Gainesville, which had been built by Black carpenters who had learned their skill as slaves.

In 1866, Carrie Jocelyn had married N.C. Dennett, a cashier at a Freedmen’s bank in Florida. (Lavinia playfully wrote to her sister about 36 year old Carrie, “Old girls do get married, you see; so don’t despair about me.” ) The National Anti-Slavery Standard congratulated the newlyweds. It described Dennett as “a well-known New England Abolitionist” and said his “life has been repeatedly threatened by the ‘Reconstructed’ whites of Florida, to whom, as an active and very influential friend of the freed people, he is obnoxious.” In February 1868, Carrie died nine days after giving birth to a daughter. The infant lived only three days. The American Missionary Magazine eulogized her:

For three years she was among our most faithful Christian teachers. Her works had borne abundant witness to her oneness with Christ, and the love for His work among the poor and needy. She had, in an unusual degree, won the confidence and love of the colored people, old and young, and with tearful interest they sought the privilege of strewing her coffin with flowers and planting trees at her grave.

Emma Eveleth continued teaching at the Union Academy until 1873 and continued her letters to the American Missionary Association. On October 29, 1872 she wrote:

Hope some of the benevolent people will think of us this year when they are making up their missionary boxes, for we are truly doing missionary work & a little help will be thankfully received…. It is only a few years since the whipping post was taken from the front of the courthouse in this place. The law is that if a colored man steal a chicken he shall be whipped & one who has been whipped shall be disfranchised. In that way they would deprive the colored man of his vote.

After Miss Eveleth departed, Black teachers took charge of all classes at the Union Academy. The school was absorbed by the local school board in 1898 and continued in operation until the early 1920s.

Sources consulted: Lavinia Goodell’s letters to Maria Frost (November 4, 1863; January 11, 1864; March 1, 1866); Letter from Clarissa Goodell to Lavinia Goodell (December 8, 1867); Joe M. Richardson, “We are Truly Doing Missionary Work: Letters From American Missionary Association Teachers in Florida, 1864-1874,” (The Florida Historical Quarterly, Published by the Florida Historical Society, Volume LIV, Number 2, October 1975); Murray D. Laurie, “The Union Academy: A Freemen’s Bureau School in Gainesville, Florida,” (The Florida Historical Quarterly, published by the Florida Historical Society. Volume LXV, Number 2, October 1986); The American Missionary, Volume 18 (1868); State Library and Archives of Florida; National Anti-Slavery Standard (December 1, 1866); Library of Congress photographs; Emma E. “Teaching Contrabands,” Principia, April 21, 1864;

Eveleth, Emma B. Teacher’s Monthly Report: Seabrook School, Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, March, April and May 1864. March, April and May 1864. MS American Missionary Association Archives, 1839-1882. Amistad Research Center, Tulane University. Slavery and Anti-Slavery: A

Transnational Archive, link.gale.com/apps/doc/FH1390142166/SAS?u=wisc_madison&sid=SAS&xid=91dc9e7d&pg=1. Accessed 14 Mar. 2021.

I was struck by the question on the Monthly Report “Do the mulattoes show any more capacity than the blacks”. The notion of an inferior intelligence of blacks, and by inference the superiority of the white race, regrettably continues to this day.

Another extremely interesting post!!! Thank you.