“Am glad Bennett is to take the case with me.”

Lavinia Goodell, January 27, 1875

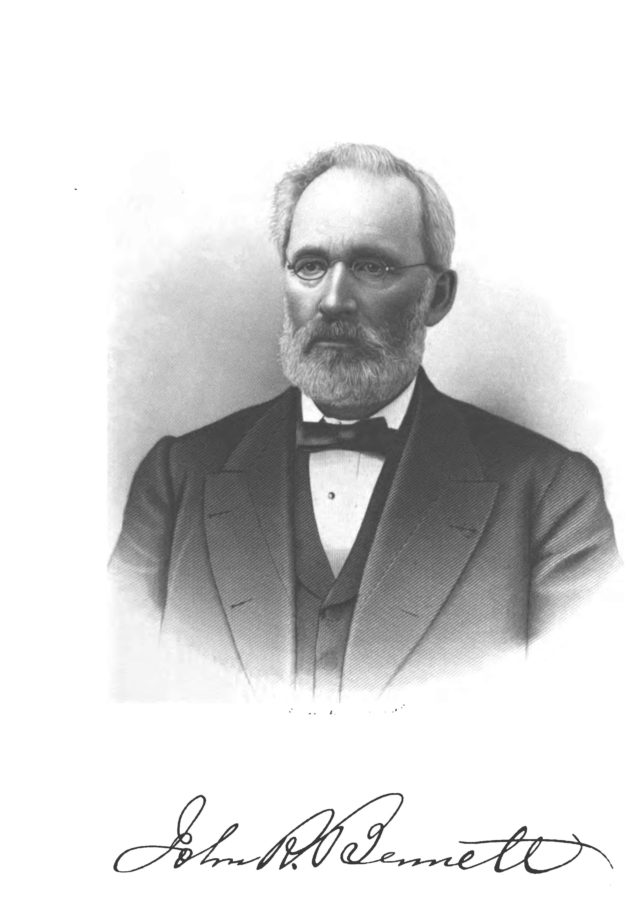

The case that spawned Lavinia Goodell’s epic battle for admission to the Wisconsin Supreme Court was Tyler v. Burrington. In November of 1874, Lavinia was retained by Lydia Burrington, a doctor’s widow who had been sued by a young woman whom the Burringtons had taken in ten years earlier and treated as a family member. The young woman claimed she had been treated as a servant and that Dr. Burrington had told her he intended to pay her for her work. Lavinia could tell that the case was likely to be a tough one, and she had only been practicing law for five months, so she looked for someone who would assist her. After Pliny Norcross turned her down, she turned to John R. Bennett.

Bennett initially said he could not help Lavinia either, but by January 1875, to Lavinia’s relief, he changed his mind.

Bennett was born in New York state in 1820 and was admitted to practice law there in 1848. He moved to Janesville later that year. In 1860 Bennett was a delegate to the national Republican convention which nominated Abraham Lincoln. Â He served as the Rock County district attorney from 1863 until 1867. He practiced law with a number of well-known attorneys, including Norcross and I.C. Sloan, who presented Lavinia’s petition for admission to the Wisconsin Supreme Court. According to a contemporary account:

Mr. Bennett is over six feet in height, is well-proportioned, and has great physical strength and endurance. In personal appearance it is said he strongly resembles Lincoln, and … has many of the mental characteristics that made the latter so great and beloved.

By all accounts, Lavinia was very pleased with her choice of co-counsel. Her diary contains numerous comments about her consulting with Bennett about the Burrington case. When the case was tried in April of 1875, both Lavinia and Bennett played an active role. They apparently both participated in closing arguments since Lavinia reported “spouting,” and she said “Bennett made splendid speech.” Unfortunately, the jury found in favor of the attractive young plaintiff.

Lavinia immediately began studying up about appeals. While she and Bennett were preparing to take their case to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, they found themselves on opposing sides of another one of Lavinia’s major cases: the Leavenworth divorce. Lavinia wrote to her sister, “Did I tell you that Bennett who is associated with me in Mrs. Burrington’s case is against me in the new case? The husband goes to him for consolation & the wife comes to me.”

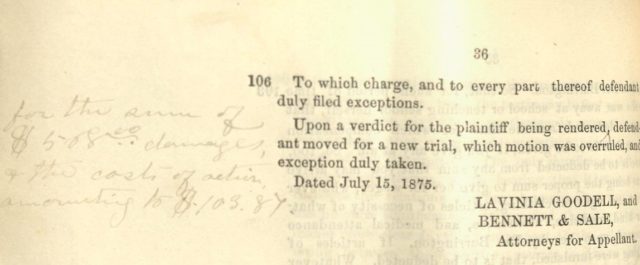

Although Lavinia was denied the right to present oral argument before the Supreme Court in the Burrington case, the briefs list her name ahead of Bennett & Sale as the appellant’s attorneys. (As a humorous aside, this photo of the last page of the brief also contains Lavinia’s handwritten addition of a few words regarding the damages her client was seeking.)

Lavinia does not mention working with or being on the opposing side of Bennett after the Burrington and Leavenworth cases were concluded.

Bennett outlived Lavinia by nineteen years. In 1882, he succeeded Harmon Conger as Rock County judge, a position he held until his death. Bennett died of a stroke in June 1899. The Janesville Gazette said:

Judge Bennett was modest and unassuming in manner, possessing quick sensibilities but with perfect self-command. Rigid and firm in his sense of duty he yet had a deep, tender and sympathetic nature and knew how to “temper justice with mercy.”

As a lawyer he was ever noted for his uniform courtesy to his brethren of the bar, and for respect to the court, as well as for his wisdom in counsel and force as an advocate…. By the strictest integrity and keen sense of professional honor he won and retained the confidence of the people. In addressing court or jury his commanding presence, earnestness and ability always inspired respect and secured attention. He was a staunch friend, and no one ever had a better neighbor. Endowed with mental faculties of a high order which were trained by extensive reading and systematic study, and gifted with a quaint and pleasant delivery he was entertaining and instructive in discourse, and was a charming conversationalist.

He was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery.

Sources consulted: Lavinia Goodell’s diaries; Parker McCobb Reed, “The Bench and Bar of Wisconsin,” (1882); Janesville Gazette (June 10, 1899); undated letter from Lavinia Goodell to Maria Frost; Tyler v. Burrington briefs (available at the Wisconsin Law Library).