“The superior physical attractiveness of the girl won her the verdict”

Dr. and Mrs. Lydia Burrington, a childless couple, took Sarah Tyler, a destitute orphan, into their home and treated her like a daughter. When Dr. Burrington died 10 years later, Sarah sued his estate for $1,100 in “wages.” Mrs. Burrington, executrix of the estate, hired Lavinia Goodell as defense counsel for the trial to an all-male jury. For Lavinia, this case proved why it was important to have women on juries.

Sarah claimed that the Burringtons asked her to do work typically performed by servants. And Dr. Burrington agreed to pay her for those services, gave her valuable gifts, and promised to leave his homestead to her.

Mrs. Burrington countered that Sarah performed only the chores expected of a daughter. She and her husband had fed and clothed Sarah, paid for her education, and allowed her to save $500 in wages as a teacher. She knew nothing of her husband’s alleged gifts and promises.

It is possible to imagine Lavinia, a women’s rights advocate, taking either side in this litigation. In her 20s, Lavinia had entered the home of a wealthy Brooklyn merchant as both a family member and a teacher for his and other children. After performing her part of the bargain, the merchant refused to pay the agreed-upon salary. She threatened to expose his deceit and forced a settlement. Read more here. So Lavinia might have identified with Sarah’s predicament.

But she didn’t. Lavinia opposed marriage partly because it deprived wives of property rights and the means to support themselves, especially after they were abandoned or widowed. She wrote and spoke on this subject often. She even proposed legislation to protect the rights of married women. Read more here. Dr. Burrington’s estate was worth about $1,500, excluding land. Lavinia understood that Mrs. Burrington, a woman in her 50s, could be impoverished if Sarah prevailed.

Lavinia embraced Mrs. Burrington’s cause and proved to be a zealous advocate. Mindful of her inexperience, she retained the skillful J.R. Bennett as co-counsel for the April 1875 trial. Then she poured herself into the case, surmounting one difficulty after another.

For several days she recorded being miserable from a large sty on her eye. She went to the office to “study up” on the Burrington case anyway.

George Bird, counsel for Sarah Tyler, tried to intimidate Mrs. Burrington by filing criminal complaint against her. The charge is unclear. However, the court didn’t take it seriously. Lavinia told her diary:

[W]ent to Justice Court with Mrs. Burrington. Quite an amusing time. Judge P. laughed at the crime. Bird didn’t appear. The sheriff was jolly.”

On February 4th, Lavinia set out for a court appearance in Jefferson County. Halfway there heavy snow forced her train to return to Janesville. The next day she made it and recorded having “lots of fun” in court over Bird’s trumped up criminal charges.

On Tuesday March 30th she received a telegram that the court would hear the case on Thursday April 1st. She and Bennett leaped into action, telegraphing witnesses, prepping them for trial, and studying briefs. Testimony concluded before noon on Friday, and the lawyers did “spouting” in the afternoon. Lavinia, confident in their defense, wrote:

Bennett made a splendid speech. The thing is in good shape now & we ought to have a verdict. The judge gives us his charge in the morning. There was a big crowd and all seemed interested. Real tired tonight.

Saturday morning she received an unwelcome surprise.

Jury were out about an hour & bro’t in a verdict for the plaintiff. Heaven knows how they could have found it. We moved for a new trial & were denied, then got a stay of proceedings and are going to appeal to Supr. Court . . . Felt real bad to lose my case, but not so bad as if I had run it alone.

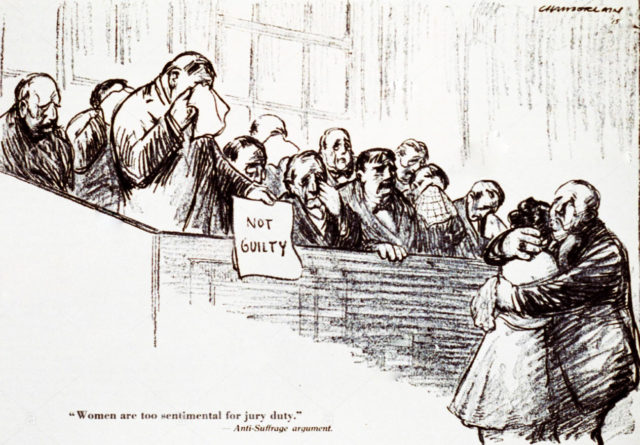

On Sunday, Lavinia attended church but was so distracted thinking about her “lost cause” that she “scandalized” her father by how little she recalled of the sermon. Perhaps she was composing “Women Needed on a Jury,” which appeared shortly thereafter in the Woman’s Journal. Without using names, Lavinia told the story of Tyler v. Burrington and attributed the verdict to the all-male jury:

The claimant was young and fair; the widowed defendant was past fifty, faded and plain; the jury were all men and in the face of law and of evidence, a verdict was rendered for the claimant, and her damages assessed at $508, much to the astonishment and indignation of all right-minded persons.

Few, if any, doubt that the superior physical attractiveness of the girl won her the verdict, and that had the jury been composed of six women and six men, the decision would have been for the defendant. So say some of the most experienced members of the bar. The defendant has discovered that she has not “got all the rights she wants,” and is now heartily in favor of having women on the jury.

The case is to be appealed to the Supreme Court, so the end is not yet.

Indeed, the best was yet to come. The Burrington appeal made the national press and ultimately established Lavinia’s place in Wisconsin legal history. Stay tuned by email, Facebook or Twitter to learn why. CB

Sources Consulted: Lavinia Goodell’s Diary January 2, 20-April 5, 1875; Tyler v. Burrington, 39 Wis. 376 (1976); Lavinia Goodell, “Women Needed on a Jury,” Woman’s Journal, Vol. 6, No. 16, April 17, 1875.