“In evening, drafted my will.”

Lavinia Goodell, July 4, 1879

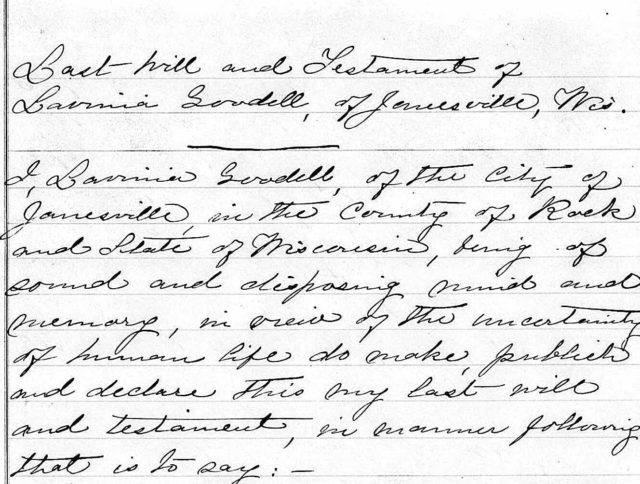

In 1879, approximately nine months before she died, Lavinia Goodell spent part of the July 4th holiday drafting her will.

There is no indication that she had previous wills. Both of Lavinia’s parents had died in 1878. She had drafted their wills. Upon their deaths, Lavinia inherited a goodly sum of money and, being a meticulous planner, she no doubt wanted to make sure that when she died, her estate would be distributed precisely the way she wanted. (Read the entire will here.)

Lavinia made several specific bequests. To her cousin Sarah Thomas, she bequeathed $1500, a gold watch, gold ring, and the majority of her books. To her friend Sarah Case, who was a telegraph operator in the village of Southold on Long Island, she bequeathed $1500 and a gold locket. Lavinia bequeathed her law books to her then law partner, Angie King, with the proviso that if Angie was no longer engaged in the practice of law at the time of Lavinia’s death, the books would go to Kate Kane, who had left Janesville and was practicing law in Milwaukee.

Lavinia bequeathed to her sister, Maria Frost, who was living in Michigan:

All my clothing, my French and German books, and such books as I have inherited from my parents; all my furniture, both household and office, all my bedding, silverware, jewelry not hereinbefore specified, and pictures, and any interest in such family papers, letters, manuscripts and family relics as my said sister and myself have inherited from our parents and now own jointly.

Lavinia’s will specified that the remainder of her estate be placed in a trust for Maria’s benefit. She named her uncle, J. Cleveland Cady, a well-known architect who designed New York City’s original Metropolitan Opera House and the south range of the Metropolitan Museum of Natural History, as trustee. Lavinia instructed her trustee to invest the funds in the manner he deemed “most safe and profitable,” and made clear that the net income from the funds be used only to benefit Maria. The will provided:

Neither the said income, nor any part thereof, shall be used in defraying the expenses, or any portion of the expenses of any member, other than herself, of the family of the said Maria; nor shall the said income, or any portion thereof, be used in defraying the expenses, or any portion thereof, of any other person than the said Maria; nor shall the said income or any portion thereof, be used to pay any debt incurred by the said Maria for the benefit of any person other than herself, the object of this provision being to secure to the said Maria, personally, the entire use and benefit of the said income, and to prevent her denying herself the comforts of life for the sake of others who are already sufficiently provided for.

Lavinia’s unwillingness to turn the funds over to Maria directly no doubt stemmed from the fact that Lavinia and her parents had a somewhat strained relationship with Maria’s husband, Rev. Lewis Frost. (Some background about the rift may be found here.) Lavinia’s parents’ wills had similarly left Maria’s share of their estates in trust, with Lavinia as the trustee. Lavinia wanted to make sure that Maria alone benefitted from the estate and that neither Maria’s husband nor her four sons got any of the money. (Later in the will Lavinia stated that “The omission of my nephews … in making these bequests, is not due to any unfriendly feelings on my part towards them, nor from any lack of affection for them; but because they are sufficiently provided for by the will of my mother; and for the further cause that, as boys, they are better able to provide for themselves than women are.”

The will provided that upon Maria’s death, the trust fund be divided into three equal parts to the causes dearest to Lavinia: “one third to be used for the advancement of the cause of woman suffrage; one third for the advancement of the cause of temperance in the direction of total abstinence and prohibition, and one third for the advancement of the cause of prison reform.”

Lavinia signed the will on July 7, 1879.

The witnesses were George M. McCausey, a dentist whose practice was in the Tallman block, where Lavinia had her first law office; Clara Normington, a physician whose office was also in the Tallman block; and F. W. H. Palmiter. (We do not have information about Mr. Palmiter. In March of 1875, the Janesville Gazette had a notice of a Mr. F. H. Palmiter taking a position as a druggist, but we are uncertain if that is the man who witnessed the will.)

Although Lavinia no doubt believed that her will provided clear and explicit instructions that left no doubt how she wanted her estate to be divided, future posts will discuss the probate proceeding, challenges to the will, and claims filed against the estate.

Sources consulted: Lavinia Goodell’s diary for July 4, 1879; Estate of Lavinia Goodell, Dane County Wisconsin Probate Court ; Owen’s Janesville city, Rock County Gazetteer, and Directory (1876); Janesville Gazette (March 3, 1875).

When I read of the objects of Lavinia’s will twenty or so years ago, I was struck by how Temperance, Suffrage, and Prison Reform defined her passions. The tales of “her boys” whose criminal cases she defended, make clear she had become a champion of the rehabilitative role our prisons should play. She understood that were mere punishment an effective deterrent to crime, there would be no crime and certainly no recidivism.