“I am dying to see a sensible woman. And they don’t abound here.”

In June 1919, Wisconsin became the first state to ratify the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote. In celebration of this great achievement many have repeated an enchanting origin story of Wisconsin’s women’s suffrage movement published in The Milwaukee Journal on December 21, 1924:

Way down in the southwestern corner of Wisconsin, the little town of Richland Center has been glorified above all towns in the state in that it is the cradle of women’s suffrage in Wisconsin.

On an afternoon in June, in 1882, a little band of women met at the home of one of their number, Mrs. Laura B. James, wife of the future Senator James, whose honor it was to carry finally Wisconsin’s ratification to Washington ”to discuss cautiously and behind drawn blinds the new and fearfully radical subject ”woman suffrage.

The story continued with members of the band travelling to Madison in September 1882 to help form the Wisconsin State Suffrage Association. Laura James and Julia Bowen were singled out as being early activists in the state and national suffrage movement by 1884.

But in 1871, more than a decade earlier, Lavinia Goodell arrived in Janesville from New York, where she had been raised to believe that women should vote. Unlike the Richland Center women, who whispered of suffrage behind drawn blinds, Lavinia boldly, publicly and nationally advocated for it. She wrote dozens of articles in the Woman’s Journal, the leading suffragette periodical published by Lucy Stone and her husband. Click here to read some of them. Her diaries note that she gave lectures on suffrage in Janesville and other parts of Wisconsin. In 1877, she recorded receiving suffrage petitions from Elizabeth Cady Stanton and openly canvassing for signatures around Janesville.

In 1878, Lavinia was one of many women around the country who petitioned Congress for the removal of their political disabilities so that they could have “full power to exercise their right of self-government at the ballot box.” This was the first woman’s suffrage amendment proposed in the United States. The one that ultimately passed, the ratification that Senator James carried to Congress 41 years later, is reportedly identical to it.

So was Janesville, rather than Richland Center, the “cradle of women’s suffrage” in Wisconsin? Far from it. In 1873, Lavinia wrote to her cousin Sarah Thomas , who lived in the East:

I shall feel miserably if you can’t come out in the fall. I am dying to see a sensible woman, and they don’t abound here. It’s perfectly ludicrous to see how scared the women here are for fear they shall do something ‘unwomanly,’ which really means something unpopular. Mrs. Beale has the most courage of any of them, but she has ballot phobia bad, and a general anxiety about her womanliness that is quite distressing.

By 1874, Lavinia had met another self-described suffragist named Mrs. Dunston. Also, she told her sister Maria: “one of our conservative neighbors surprised me by saying, referring to my [law] business, I think you ought to vote. So you see I am educating people up to higher ideas.”

Still, Lavinia had discouraging encounters, like one with Mrs. Hoppin in March 1875: “Mrs. H and I had quite a hot discussion on woman’s rights. She horrified me with such heathenish notions that I have been suffering ever since from the painful impression she gave me. It makes me more homesick than anything else to have women so content with their degradation.”

Without further research, it is hard to identify Wisconsin’s first suffragists. One of Lucy Stone’s biographers writes that she lectured on suffrage in Racine, Milwaukee, Madison and Janesville as early as 1856. She was “completely discouraged” after the Milwaukee event because only 200 of the city’s 35,000 residents attended. But even back then she was able to find two legislative assemblymen to present her petition on women’s suffrage to the Wisconsin Legislature, where it “fostered a rousing discussion” and three men actually supported it.

The point is that while the Richland Center women deserve credit for their contributions to Wisconsin’s women’s suffrage movement, strong-minded women like Lavinia Goodell were paving the way long before their 1882 huddle. If any readers have information on Wisconsin’s suffragettes during the 1850s through 1870s, please email us bibliographic references or post a comment below. And if researchers at the Wisconsin State Law Library or Legislative Reference Bureau are following this digital biography, we’d love to see the petition on women’s suffrage that Lucy Stone presented to the Wisconsin Legislature in 1856. CB

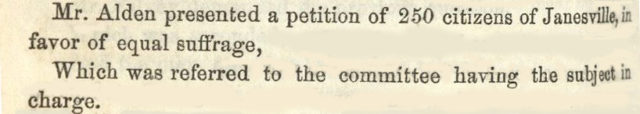

Update: Kudos to Michael Keane at the Wisconsin State Law Library. He reviewed the journals of the Wisconsin senate and assembly for 1856 and found that a Mr. Alden had presented a petition for equal suffrage signed by 250 citizens of Janesville. Wow!

Sources consulted: Lavinia Goodell’s letter to Sarah Thomas, Aug. 18, 1874; Lavinia Goodell’s Diary, May 26, 1874, March 26, 1875, March 24 and 30, 1877; Mary Elizabeth Hussong, “Richland Center, the Cradle of Suffrage in Wisconsin,” The Milwaukee Journal, Dec. 21, 1924; “The Sixteenth Amendment in Congress,” Woman’s Journal, Vol. 9, No. 2, Jan. 12, 1878; Sally G. McMillen, Lucy Stone: An Unapologetic Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015) at 133-134; National Women’s History Museum’s “Woman Suffrage Timeline.”